Broadway review by Adam Feldman

In the 1989 movie Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter played a pair of dim teenage rockers who traveled through centuries and around the world and even—in the film’s 1991 sequel, Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey—beyond this mortal coil. So there’s a satisfying snap to the joke of casting them, in Jamie Lloyd’s revival of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, as the long-suffering tramps Estragon and Vladimir, two of the most immobile characters in world drama. Eternally, it seems, they await a mystery man who never appears, and yet they never learn; they are locked in a cycle of forgetting and resetting. “Well, shall we go?” says Reeves’s Estragon. “Yes, let’s go,” replies Winter’s Vladimir. But Beckett’s famous stage direction keeps them in their place: “They do not move.”

This casting is more than just a stunt, though; the nostalgic affection that the audience holds for Reeves and Winter has certain salutary effects. “Together again at last! We have to celebrate this,” says Vladimir at the top of the play; the audience is there for the reunion party, and it arrives with the gift of a prior sense of these two men as friends. When they mention having known each other “a million years ago, in the nineties,” the line hits differently than it did when the play made its Broadway debut in 1956; when they embrace, it has an extra level of sweetness. They have history with each other, and with us.

Waiting for Godot | Photograph: Courtesy Andy Henderson

But time has caught up to these erstwhile time travelers. Winter still sometimes looks boyish, but his face has more lines and his eyes are more sunken; Reeves, in a grey beard, looks gaunt and at times almost haggard. (His hair, mind you, remains long and raven black.) In a play that deals centrally with exhaustion and age, watching these actors 35 years after the youthful exuberance of Bill and Ted adds an extra degree of poignancy.

As for their performances: Reeves and Winter are very much giving it the old college try, which is to say that they’re older but from time to time their acting is a little collegiate. Winter is touching as Vladimir, or Didi, whom he imbues with lovely sincerity and feeling—especially in his longing for companionship with the pricklier Estragon, or Gogo (who is constantly trying and failing to go). Only when Lloyd’s staging gets self-consciously serious does he slip into earnestness. But Reeves is often stiff and underexpressive; Beckett’s language fits him as ill as his suit, which is short at the limbs but baggy at the waist. (He sometimes suggests a sad Keanu meme come to life.)

Waiting for Godot | Photograph: Courtesy Andy Henderson

I wish that Lloyd’s production leaned harder into the Bill & Ted resonance; aside from one signature air-guitar riff, which the audience eats up, it doesn’t fully commit to its bit. Winter and Reeves’s teamwork is at its best when at its goofiest, and Waiting for Godot, despite its rather bleak reputation, is loaded with dumb humor. Beckett offers his existentialism by way of vaudeville comedy, the lower the better: burping, farting, stinky feet, bad breath, slapstick falls, pants falling down. Their most memorable moments here are silly ones, such an extended gag in which they pass around their Laurel and Hardy–style bowler hats.

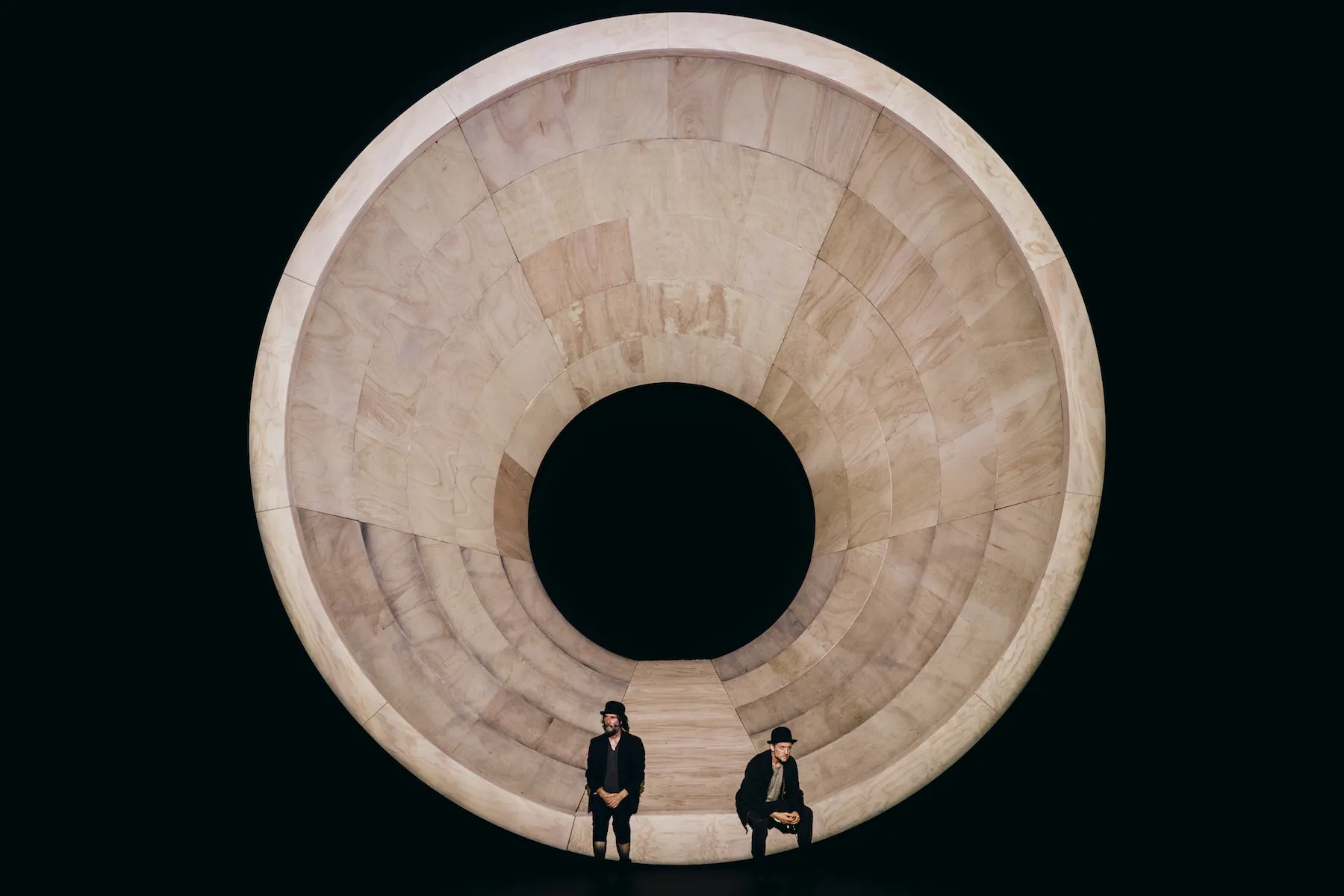

This revival’s real strengths are elsewhere, however. Lloyd’s choice that all of the props be mimed, from turnips to whips, emphasizes the ephemerality of the play’s world and sometimes yields fascinating results. And Soutra Gilmore’s striking, beautiful set is radically different from the usual ones, which have tended to abide by the conventions set by the persnickety Beckett estate. The set’s core elements are still as the script specifies: “A country road. A tree.” But whereas other productions put the tree in the road, this one blows that whole idea inside out: The road appears to be inside the tree, which is rendered nonliterally as a giant tube of polished wood. The rise and fall of the sun is suggested by the movement of large Suprematist shapes.

Waiting for Godot | Photograph: Courtesy Andy Henderson

Another kind of inversion is detectable, perhaps less intentionally, in the balance between the two tramps and the play’s other main characters: the rich and abusive Pozzo (Brandon J. Dirden) and his beleaguered servant, Lucky (Michael Patrick Thornton), who cross paths with Didi and Gogo in the first act and then return, in much diminished form, in the second. I’ve seen productions in which these characters’ scenes didn’t land; what I’ve never seen before is one in which they dominated the show so completely. Both of these actors are superb. Dirden’s Pozzo is a preening Southern landowner and slavemaster—that Dirden is Black adds an extra zap of meaning—with darting eyes and highly charismatic confidence in the value of his pomp. Thornton gives a spectacularly effective account of Lucky’s one big speech: a logorrheic outpouring of pseudoacademic gobbledygook (“in view of the labours of Fartov and Belcher left unfinished for reasons unknown…”) that captures, in his performance, the shallowness and the futility of trying to sound profound, as well as the toll that sustaining such attempts can take on the would-be thinker. Thornton’s wheelchair is employed inventively throughout the production.

The pleasant prospect of seeing Reeves and Winter together makes this production to some extent critic-proof—and anyhow, this is a play in which “Crritic!” is the worst insult that Estragon can think up. But although Reeves and Winter are the main reason most people will go to this Godot, it is this revival’s other assets—the direction, the set and above all Dirden and Thornton—that keep it from being an exercise in meta stasis. For me, those elements make the production worth seeing, but one nice thing about Waiting for Godot is that it just keeps coming. This is the play’s third Broadway revival in the 21st century, and there have been numerous Off Broadway versions in recent years, too. If you decide to skip this one, you won’t have to wait very long for another.

Waiting for Godot. Hudson Theatre (Broadway). By Samuel Beckett. Directed by Jamie Lloyd. With Keanu Reeves, Alex Winter, Brandon J. Dirden, Michael Patrick Thornton. Running time: 2hrs 5mins. One intermission.

Follow Adam Feldman on X: @FeldmanAdam

Follow Adam Feldman on Bluesky: @FeldmanAdam

Follow Adam Feldman on Threads: @adfeldman

Follow Time Out Theater on X: @TimeOutTheater

Keep up with the latest news and reviews on our Time Out Theater Facebook page

Waiting for Godot | Photograph: Courtesy Andy Henderson