[title]

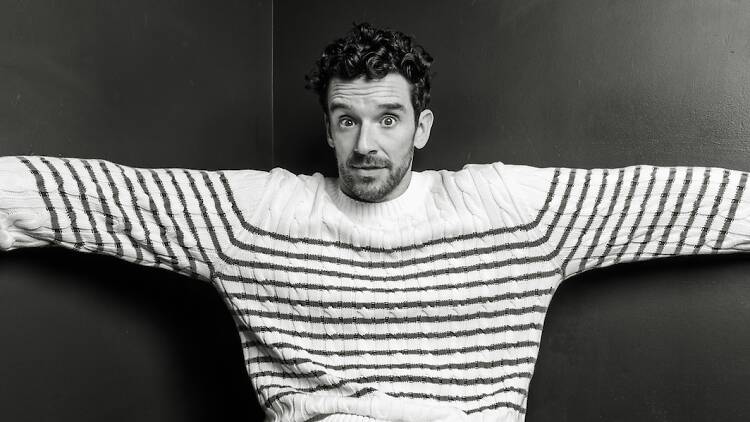

Michael Urie is a very busy boy. One of the finest comic actors of his generation, he's worked steadily since his breakout role as Vanessa Williams's assistant, Marc St. James, on TV's Ugly Betty, but his dance card has been especially full of late. Urie has appeared in six Broadway shows in the past seven seasons, from his star turn in 2018's Torch Song to his recent summer stint as Mary's Teacher in Oh, Mary!; meanwhile, he has played a central role in the Apple TV+ series Shrinking, earning his first Emmy nomination earlier this year. But although he is best known for comedy, Urie has a background in classical acting, and even won an award for it when he was at Juilliard. That side of his training is now on display in Red Bull Theater's production of the history play Richard II, in which he has the demanding title part: the young 14th-century English king whose fall helps ignite the Wars of the Roses. We spoke via Zoom recently about his career, his influences and the challenges of Shakespeare.

It feels like you've been in so much recently. Are you exhausted?

My last week in Oh, Mary! overlapped with the first week of rehearsals for Richard II. I've done that before, but I'm 45 now, and it's harder than it was even two years ago when I did it for Once Upon a Mattress and Spamalot. And that was really hard: two musicals. So I’m a little tired. But it's good. This bounty of work is something I’ve always been trying to get; being able to go between varying roles was the dream when I was getting out of school. I'm very lucky—especially with something like Richard, which I kind of spearheaded myself. I've been looking for a way to play this part for many years, and it's happening with the director I wanted and an amazing cast. So I gotta stay awake and healthy and excited.

Now you’re playing Richard II, and a few years ago you played Hamlet in Washington, D.C.—both of which are huge, tragic, verse-heavy parts. It's striking that when you’ve chosen to do Shakespeare, you've been drawn to these roles instead of the big comic ones.

That's interesting, yeah. But I’d certainly love to play Bottom [in A Midsummer Night’s Dream], or Benedick in Much Ado, or Berowne in Love's Labour’s. Those are parts I'd love to play too.

What draws you to classical theater generally?

I didn’t grow up on it. I kind of grew up in front of the television. We went to see Dallas Shakespeare Theater when I was a kid, but I didn’t know what they were talking about—I couldn’t follow it at all. Then in high school, we did a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and I really fell in love with it.

Whom did you play?

I played Demetrius. It was a great production for our class, and we found so many funny things in it. The lovers’ quarrel can really steal the show. I remember falling in love with the unexpected of Shakespeare. Sure, we’re drawn to heads on pikes or fairies or sword fights, but the best stuff, the reason we keep coming back, is the psychology, the romance, the poetry. That didn’t come naturally to me. It wasn’t until I started speaking Shakespeare that I started to understand poetry and verse. And then at drama school, we spent so much time on Shakespeare—it was probably more than half the training—and I realized it’s not meant to be read, it's meant to be spoken. When I speak it, I understand it, and when I hear it spoken well, I understand it. That’s what brings me back every time: It's so visceral, and when it sings it's just incredible.

And there’s something inherently musical built right into the language of these plays, because a lot of it is written in meter. I may be wrong, but I think Richard II is entirely in verse?

You're absolutely right.

Because there are no commoners in it, only nobility.

Well, there are the two gardeners. But even they speak in verse! Which is a comment on how in this world, even the commoners are smart—maybe even smarter than some of the schemers.

Richard II is not staged super often. Is that part of its appeal to you—that it's not quite as familiar, or as burdened by past versions?

Yeah, I think so. In New York, when you do Shakespeare, there's a feeling that you need to have a real take and show the audience something they haven’t seen, because it’s such a smart audience—the theatergoing audience Off Broadway are almost professionals. They see so much. Which is why working with Red Bull is so great: They have such a dedicated audience but they’re also always looking to expand the audience. And I think our amazing director, Craig Baldwin, has found a way to do this play in a way that the purists will love and anyone who comes in not knowing anything will still have a great entry point. They'll be able to hear it and follow it in a wonderful way.

One of the challenges of doing the history plays is that there's so much English dynastic history embedded in them—these genealogy tables that are really tricky to follow if you haven't learned about these things all of your life. Like, who is John of Gaunt again? Who is Bolingbroke? And there are speeches explaining those things, but making those speeches unboring can be a real challenge.

When we rehearsed the early scene when I first mention Bolingbroke, I asked, "How are they going to know who this is?" And Craig said, “You just have to imbue the name with a charge. They’re not always going to know exactly what you’re talking about, but if you know what you're talking about, they're going to know there's something happening there. They're going to recognize the drama or intrigue or betrayal or whatever is happening, and they'll be able to track that.” He’s right. And I think that’s part of why a role like this is a good fit for me, because I have to look up almost every word I say. It doesn't come naturally when I read it. Once I speak it, it feels organic, but I have to learn to make it make sense to myself. And people are gonna understand it better, I think, because I'm working through it that way. And one great thing about these big characters in Shakespeare is that that’s what they're all doing: They're all working through something. They’ve got big problems and they spend the whole play working through them.

In the academic discourse around Richard II, there’s quite a lot of discussion about the process you’re describing—about how he’s trying to find himself, and find himself through language. One of my favorite Shakespeare scholars, Harold C. Goddard, makes the point that at the beginning of the play Richard seems drawn to poetical fancies that he’s too callow to pull off, so they just seem empty. For example, in the speech when Richard banishes Bolingbroke, the grammar of his elaborate metaphor doesn’t even track: He warns of the danger of waking an infant peace, but then ends up saying that this peace, once disturbed, will “from our quiet confines fright fair peace.”

“And make us wade even in our kindred’s blood.”

Right. But he loses track of what he’s saying midway, and ends up saying that peace will scare peace away. Which makes no sense.

That’s very interesting.

But his command of language changes. By the end of the play, when he’s in prison, he’s very eloquently and touchingly poetic.

Yes. His introspection in prison is so clear. We're actually using prison as a framing device. It's a very cool conceit that Craig came up with: The play starts in prison, with the speech where he says, “Thus play I in one person many people.” The idea is kind of that it's all him recounting what happened that got him here, or imagining what may have happened in the scenes he's not in. And in our version, the thing you’re talking about, getting lost in his own language, is less about being immature and more about hiding the fact that he was actually involved in the murder of [his uncle] Gloucester—which is kind of the inciting event of Richard II, though it happens offstage before the play starts. Gloucester was the next guy in line to the throne and he died under mysterious circumstances. Was Richard involved or was he not? His dancing around with this flowery language, in our version, is about avoiding the accusations.

So he stumbles because he’s guilty, and because he’s lying.

Exactly. And that’s a hard thing to [communicate] when you're speaking this beautiful Shakespeare. But Shakespeare helps us. It's wild to think that 400 years ago, he knew all this and was able to write it into the words—not just the stage directions, like we often see now, but the words themselves. The words and the meter tell you when something is off, when something’s not quite accurate.

Leading with that line by Richard in prison—about being one person playing many people—is apropos, because this production was initially slated to be a solo reading, right? But now it’s a full production?

Yeah, that’s right. I’ve been working on trying to get this Richard II going for a long time. It was originally announced as a one-man Richard II; we were going to workshop it and do a reading for just a few audiences. But the announcement made it look like a full production, and people got excited. I heard from a lot of people who were like, “This is so cool,” and I think Red Bull did too. So Jesse Berger, because he's an intrepid producer, was like “Should we just do it?” This was not that long ago—maybe May or June. And I said, “I’d love to, but I don’t think I can pull off a one-man Richard II by October. But I could just play Richard if you hire other actors.” And luckily Craig Baldwin, who had the original one-man concept, was game to pivot; he was like, “Yeah, I think we could definitely do a full production.” And Red Bull made it work.

I’ve always really liked what Red Bull does. It’s never boring, but it’s not just scattershot radical change for its own sake. It cares about the text.

Yeah, and they don’t dumb it down. They try to make it accessible, easy to follow—as we all should—but they also respect the audience’s intelligence. They trust people to lean in and listen. When I got out of school, all I wanted to do was theater, but I couldn't get any work in New York. But Red Bull hired me! I was actually doing a Red Bull show when the casting director from Ugly Betty came.

Which show was that?

The Revenger’s Tragedy. That was probably the coolest thing I’d done in theater at that point. And then when Ugly Betty got picked up, I was doing Othello, Midsummer and Titus Andronicus in rep at the Old Globe in San Diego. So for a month I was doing double duty: I would do Othello and then drive to L.A., shoot all day, then drive back to San Diego and do Midsummer.

Richard II has inspired a lot of critical discussion about gender and sexuality, tied to the perception that Richard is not strong enough to be king. He arguably has an Edward II quality, and the text seems pretty suggestive when his courtiers are condemned for corrupting him. [“You have in manner with your sinful hours / Made a divorce betwixt his queen and him, / Broke the possession of a royal bed…”] Is that an element in this version?

Big time. We’re leaning into that: The idea that Edward, the previous king, was a great warrior, and my father, Edward, who died before he could be king, was also a great warrior. So the assumption was that I would become one too, and that’s why the throne came to me. But then I grew up to be, you know, this little flower-picking fancy boy—someone who loves his crown and scepter and avoids any kind of physical conflict. He’s all poetry, no battle. He’s not a hawk. And we’re giving it a sort of 1980s New York aesthetic—I mean, it sort of sounds and looks like that, but it's also still medieval England.

In other words, it's an Off Broadway Shakespeare production!

Right. [Laughs.] It’s kind of daunting, but then the text can hold all of that at once. And because we're setting it into the 1980s, we can really lean into the idea of open queerness or how queerness becomes an open secret, which is kind of where we are in this play. Like, Richard has a queen, and she's great. Right? He picked the most fabulous queen he could. But he also has a bunch of gay guys around.

And then he and the Queen have a lovely, weird goodbye scene that is quite formal and ritualistic in a way but also very touching.

Yeah. You don't get much of them for the whole play, and then you get this beautiful, flowery scene. I think he just chose the most wonderful, fabulous person he could to be his queen. They have this sweet, playful relationship. But it's not the same kind of relationship that he might have with somebody else that he keeps close to him.

You’ve been out of the closet basically from the beginning of your career, and you've been at the forefront of a 21st-century generation of openly gay actors who often play gay roles. And that corresponds with an expansion in the number of roles; it’s possible to make a career today just playing gay characters. I was thinking about this shift when Jeff Hiller won his Emmy Award, and the other three gay nominees in his category, including you, seemed so genuinely pleased. There was a real sense of community there.

It was so interesting, that moment. Of course in my head I’m thinking, “Are they going to say my name?” It was my first time ever being in that situation, with a camera on my face as someone’s name was about to be announced. All I could think was, “Keep smiling. No matter what they say, keep smiling.” But it was going to be a fake smile. I mean, I would’ve been happy if Harrison [Ford] won because we’re on the same show. But it’s a weird, cruel thing. It’s like Survivor meets The Hunger Games. They put a close-up of your face on TV and anyone can pause it and see what you did. And of course we all love when they're disappointed or jokingly mad. I'll never forget Kathy Bates ripping up her speech.

Or Jackie Hoffman yelling “Damn it!!” at the Emmys.

Yes, yes, yes. So funny. God, I love that. But then they said Jeff’s name, and there was that totally organic reaction from all of us, just joyfully. We had no idea that would happen. And, I mean, Jeff Hiller is a genius. When he got nominated, I thought, “Oh my God, Jeff—he should win.” He is amazing. And his show [Somebody Somewhere] is over now and it shouldn’t be; it should run forever. It was such a special, beautiful show, and what he was doing—we’d never seen a person like that on TV before. I'm so proud of what we are doing on Shrinking, and what Bowen Yang does on SNL is amazing, and what Colman Domingo did on his show was brilliant and he does so much cool work. But what Jeff did was so new: that person playing that guy on that show about real humans. There are so many shows that are idealistic, or super glossy, or satirical. That show was totally real. So I think we were all just proud. It felt like we all won, as people. But also, we kind of all came up together. I’ve known Jeff for years. I haven’t known Bowen and Colman for as long, but I know them. And to your point: Things have changed so much over the last 18 or 19 years, since Ugly Betty came on TV. The fact that there were even four gay actors eligible for Best Supporting Actor in a Comedy, much less win…

Gay guys were a majority of the category!

Exactly! We were the majority. And you sort of think, “Well, we’re gonna cancel each other out and one of the straight guys will win.” But then they called Jeff’s name. And maybe because this demographic is still relatively new and young, it was exciting for all of us. Maybe one day we’ll get jaded and bitter, but not right now.

Well, he doesn't have a chance of winning again next year. So it's anyone's game.

True. [Laughs.] That's true.

This is part of the same broader topic: I may be misremembering this, but I feel like when you started in Ugly Betty, your role wasn’t intended to be as large as it became?

Yeah. He was only gonna be in the pilot. Vanessa [Williams]’s character was going to have a different assistant every episode.

Like on Murphy Brown?

Exactly. I didn’t have a deal. I was just happy to be in a pilot. So I really went for it. Eventually, they decided to put me in every episode of Ugly Betty—in part because they liked what I was doing, but also because Vanessa was so generous and gracious. I was doing this whole act where I would mimic her behind her—I’d stand like her, move like her—and someone told her I was doing it. She didn’t know, because I was behind her! So she came over and was like, “Hey. Hey. I hear you’re doing me behind me.” And I was thinking, “Well, I’m fired.” But she said, “What else can I do that you can do?” And suddenly, I was pitching her physicality that she could do that I could then mirror behind her. And that’s something we could imagine a lot of actors not enjoying—someone essentially making fun of them. But she was all in. I owe her a lot.

So you get this pilot opportunity and you have nothing to lose: You’re gonna be this somewhat queeny, excitable young guy for one episode. But then they keep you on the show, and suddenly you’re doing this all the time—and it's your first big role. As a gay actor, did you worry about how that might shape the perception of you in the industry?

Like, that I would be pigeonholed? Yeah, I definitely thought about that. But I was so happy to have a job, and Ugly Betty was a big hit right away. I think there was part of me that thought it wouldn’t matter since I just wanted to do theater anyway. And I knew it wouldn’t hurt me in the theater—in fact, it would help. I could go back to New York after the TV show's over and get into rooms I never got into before, like Michael Greif’s production of Angels in America and the Daniel Radcliffe revival of How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. I was able to do that kind of stuff because of TV. So maybe I would have worked more on TV if my breakout role had been less flamboyant or less eccentric, but I wouldn't change a thing. I've gotten to play so many amazing parts in theater in New York and elsewhere, and I get to go back to TV whenever they need me. That’s the coolest part: I'm not out there pounding the pavement for every TV show. When it's real, it's real, and when they come for me, they really come for me.

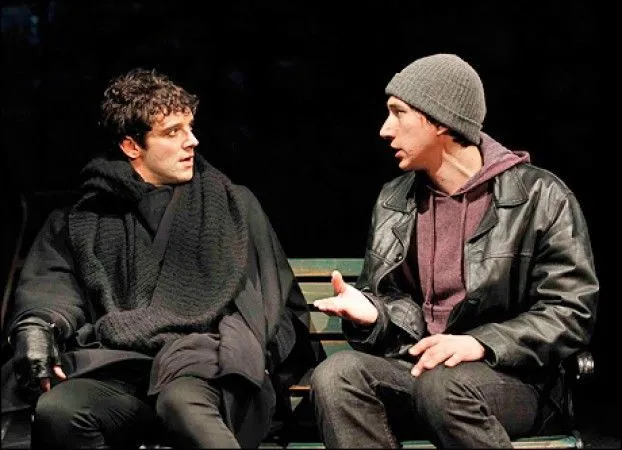

In New York, you’ve gotten to play the lead role in revivals of what may be the two most important gay plays of the past fifty years: Harvey Fierstein’s Torch Song Trilogy and Tony Kushner’s Angels in America. I loved you in that revival of Angels at the Signature.

I can’t believe you were there! That’s so amazing.

Yes! I had seen it when it opened with Christian Borle as Prior, and then I went back when you replaced him. You were so good, and it’s such a crazy demanding part.

It’s a huge role. It’s so big and so epic. We did eight shows a week, and on weekends we did two marathon days—so we’d do the whole play on Saturday and Sunday, which was kind of amazing. I always thought we should just do four days a week and only do marathons, but obviously that doesn't work for the audience. It was incredible. I had auditioned for it, and I think it was down to me and Christian Borle. I remember my audition vividly, because it was a big deal for me. I think we were still doing The Temperamentals, or we had just finished, and Michael Greif came to see the show. He was so great and really generous with his time. I went in a bunch of times, and the last time, Christian Borle was in the waiting room. I remember thinking, “Oh, this guy. Yeah. He’s really good.” So he did it. But it ran for a long time, and then they brought us in—me, Adam Driver, Sofia Jean Gomez and Keira Keeley. We were new. Billy Porter stayed, and Bill Heck and Frank Wood.

But then a bit later, Jonathan Hadary took over as Roy Cohn! I was sorry I didn’t get to see him.

Yes, Jonathan Hadary came in for the very last extension. He was so good, and totally different than Frank. Frank was doing this incredible, chameleonlike grotesque thing. And then Jonathan came in and was very easy, very himself—it was like the guy just walked onto the stage. Two very different takes, both totally brilliant. We shared a dressing room; Prior and Roy Cohn shared the tiniest dressing room you’ve ever seen. Because of the lesion makeup. They kept it in the same room.

And your Louis was Adam Driver, who suddenly seemed to be in everything around that time.

He was having a real moment, and he was about to blow up. In fact, while we were doing it, we were both waiting on pilots. Mine didn’t get picked up. His was Girls. [Laughs.] While we were doing Angels, he missed a day to go shoot a Clint Eastwood movie or something. He was awesome, and so great to work with. He had such incredible instincts. One thing that I’ve always applauded and remembered: Obviously he’s straight, and just wildly masculine—not an effeminate bone in his body—

And not a conventional Louis!

No, not conventional at all, because he’s huge, and there are all these lines about Louis being tiny because it was Joe Mantello who played him originally. But here’s this huge guy who could pick us all up. I just so appreciated that Adam didn’t try to affect himself in any way. He didn’t put on a lisp or a limp wrist. He had this great confidence about himself—he was just like, “I could be gay. This guy could be gay.” And of course he could. We’ve all met guys who don’t come off as gay, but are gay. He was just incredibly intelligent, had a great way with the language, and didn’t put on any airs. I always thought that was so cool. We’ve all seen straight actors play gay and, like, go for it, and there’s this sense that they don’t think we’d buy it if they didn’t. But I get it. And, of course, the reverse is true too—there’s always a microscope on gay actors playing straight to make sure they can pull it off.

Right. I was watching an interview with Jeff Hiller on the Howard Stern show the other day, and he said something to the effect of, “I don’t necessarily think I need to play straight. There are a lot of different kinds of gay guys, and I can play a lot of them.” And not just the one type that he’s tended to get cast as. But also, as you said about Adam, not all gay guys read as gay immediately—and there are plenty of straight guys who do read that way. Like, Prince Dauntless in Once Upon a Mattress is a mama’s boy, but that doesn’t make him gay—you still believe he could end up with a girl like Fred, who’s pretty butch. They balance each other out.

Totally. They yin and yang; he’s afraid of his own shadow, and she’s swimming through swamps. So they fit together really well. But that’s really interesting, what Jeff said, because that’s exactly how I’ve felt. When I was in Ugly Betty, people I respected very much were telling me, “This is wonderful. This role's gonna do great things for you. But then that's it. You can't do any more gay roles after this.” But then I did The Temperamentals in my hiatus from Ugly Betty, and my character was Rudi Gernreich, a gay guy in fashion. And on Ugly Betty, I played Marc St. James, a gay guy in fashion. But they couldn't have been further from each other. The styles were so different. One was a comedy, one was a drama. One had camp, one had history. And that's when I was like, The idea that you can only play gay one time is total bullshit! Because there I was, playing two characters that seem the same on paper, but are actually completely different. We contain multitudes. And I've certainly gone back to the sort of campy thing that we did on Ugly Betty, and I've gone back to the dramatic well of The Temperamentals. But I don't feel like I've played the same character twice, you know?

And you did get to play Arnold in Torch Song, which is both camp and dramatic.

Totally. That show had it all. I always told Harvey, “When am I ever going to get to do all these things in one play again?” I got to be in drag. I got to have a knock-down-drag-out fight with my mother. I got to get the cute guy. I got to be a father. I got to do everything, all in one night. I always think about how many plays couldn’t have run if Torch Song hadn’t walked.

And skipped! And run!

Exactly. Including Oh, Mary! And Cole won a Tony, just like Harvey did—both their performances and their plays were lauded. So doing Oh, Mary! felt like a full-circle moment—getting to be part of our comedic canon.

And it must have been nice to get to pop in and out of the production. In a Broadway run, you often have to make a longer commitment. Plus, the teacher role in Oh, Mary! is really fun, but it’s manageable if you’re preparing for a demanding role like Richard II, right?

Totally. It fit perfectly. Richard was already in the pipe when the Oh, Mary! offer came in, and I was like, Am I crazy to do this? But it's not a huge role. There's not a lot of stage time, or anything like the crazy volume of dialogue that I have in Richard. So I thought, yeah, I think I can pull this off. Plus there's Shakespeare in Oh, Mary!—this guy teaches Shakespeare. So it felt like a natural primer.

You had some great physical comedy in Oh, Mary!, which is something I’ve often admired in your work—in musicals as well as in plays like The Government Inspector and Jane Anger. I don’t know if there’s one answer for this, but when it comes to those physical moments: Do you actively look for ways to incorporate them? Or is it more about looking at the lines and finding ways to push them out?

Great question. I think it’s organic, but I’m always willing to try. Like, when I was doing Hamlet, which is not a comedy, our version was kind of funny—to the chagrin of some people, but we were kind of going for it. I feel like if the audience at a Shakespeare play is laughing, that means they’re following it; the more we can make them laugh, the more they're going to remember and understand it. So I was all game for a funny Hamlet, and Michael Khan, who directed it, let me do some silly things. At one point I got chased by Claudius’s goons onto this great big scaffold, and I punched a guy and then ran. And I was like, “You know what I could do here? I could jump off this railing and slide down this pole.” And Michael kind of looked at me and said, “Okay, fine. You can do it. You can do it for the people in the audience who are waiting to see you climb down a pole.”

And Hamlet doesn’t have an equivalent of the Porter scene in Macbeth—it doesn’t really have a built-in comic break.

No. Polonius is funny, of course, but he’s not a clown. And when Hamlet goes mad, that’s often played as funny. But it’s not until Osric comes in at the very end that you really have a clown—and we weren’t playing him as a clown. We had him as a very serious character. So I thought, “Okay, then I’ll be funny. I’ll climb around and fall down.” When I was growing up, my heroes were people like John Ritter, Martin Short, Kevin Kline—great physical comedians who always played with their whole bodies, even on camera. They found ways to do that. And on Ugly Betty, we did a lot of wide shots and walk-and-talks, so I could do a lot of physical comedy on that show. I think it’s just part of how I work.

And one good thing about physical comedy is that if it’s done well, it tends to endure, because it’s so primal. A lot of other humor, even the best of it, gets dated more quickly.

Totally. That's such a good point. If you listen to Steve Martin's old comedy routines, the audience is just dying, but it doesn’t necessarily make us laugh. But if you watch Steve Martin in The Three Amigos do that scene when he's in chains, that is still hilarious. Or have you seen that Blake Edwards movie with John Ritter, Skin Deep? There’s a great scene where he’s running around in the dark wearing a glow-in-the-dark condom. Or there’s another scene where his ex-girlfriend gives him an electric shock and for the next two scenes, he’s still feeling the effects as he’s, like, walking down the street.

Did you watch any actors in particular to try to figure out how they did it?

Well, there was Three’s Company, which I watched on Nick at Nite. And John Ritter was in the movie version of Noises Off, with tons of other cool actors, and that was a big one for me that I watched over and over and over again. There's a lot of great physical comedy in the movie Clue, in what Tim Curry does. And then when I got into theater, it was Bill Irwin. I think this kind of goes back to your question about what comes first, the bit or the idea. Again, I think it’s sort of organic. You see something and you think, “I want to do something with that. I want to figure this out.” In The Government Inspector, the set had two stories and no visible stairs. There’s this huge drunk sequence that ends the first act, and the script says he stumbles offstage and you hear a big crash. And I was like, “That’s not gonna work. I need to fall right off this thing.” So the fight people helped me figure out how to fall off the second story. With Jane Anger, it was similar. At the end of the play, I got my arms chopped off and I fell out the window, so I was like, “Okay, what's the funniest way to fall out of a window safely?” You get a kernel of an idea and then it kind of grows. I don't know if there's gonna be any physical comedy in Richard II, but if there is, I'll find it.

Richard II is playing at the Astor Theatre through December 14, 2025. You can buy tickets here. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.